Each year, many millions of spectators all over the world look up at evening skies for exciting displays of pyrotechnics. Some viewers choose to bring cameras, and of those, many are falling short of capturing the "Oohs!" and "Aahs!" associated with fireworks. With a little help, the guesswork will be gone, and your images will be the ones your family and friends will be looking forward to after the show.

First, the materials:

Camera. Preferably one with "bulb" mode. White balance control a plus.

Point-and-shoots, turn off the flash! On DSLRs, setting the camera to "sunny" will get the closest color representation. Point-and-shoot users might have a choice to make here. Can your compact camera choose to use whatever aperture, focusing, and color temperature you tell it? For example, can you tell the camera to use the sunny setting while still controlling the aperture and where you focus? If so, you're all set, and we'll get to the other settings in a bit. If your point-and-shoot is more limited, choosing "landscape" mode, typically indicated by mountains on the dial, will choose a small aperture, and that will be good for now.

Tripod. Or something sturdy to lean on, like a big tree or telephone pole.

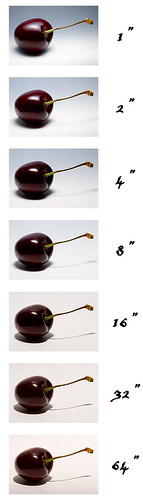

The exposures will be several seconds long, and the support of a tripod will be best. Compact camera users can sometimes get by with a tree, telephone pole, rock, or otherwise immovable object, by using it as a static monopod. The camera gets pushed against the "monopod", and with ample support, a light shutter finger, and steady hands, the results should be at least okay for a majority of exposures.

Cable release.

SLR users, get one. Especially if you already have a tripod. Point-and-shoot users, the cost of a cable release might not be justifiable, but again, if you have a tripod, and a cable release port, the investment is a good one. The added bonus with a compact camera and the above "static monopod" is using a cable release means no added shake from releasing the shutter, increasing the keep ratio of photos even more.

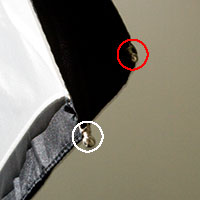

Black board. Optional.

A dark object, like a black piece of foam core, or a black bag, will enable the ability to "close" the shutter to ambient light without releasing the shutter. Why? This allows the capture of multiple volleys in one exposure, without washing out the scene in ambient light.

Now that we know what to use, learning how and where to photograph fireworks are the next steps in capturing great pyrotechnic imagery.

DSLR users have it easy. Simply set up your camera with tripod and cable release, and start with these settings: ISO100, f/11, bulb exposure, manual focusing. Shift your aperture for fine tuning. After dusk, there's rarely times where larger than f/8 and smaller than f/16 will be necessary. For focusing, choose either infinity, or hyperfocally. Choose before it gets dark, and make a test exposure to check whether your focus produces sharp images.

Compact shooters, set up your tripod and attach the cable release, if you have them. Set your ISO to its lowest setting, usually 100 or 200. If you have aperture control, figure out your minimum aperture, then stop up one stop. For instance, if your aperture goes down to f/11, set it to f/8; f/16 would stop up to f/11. However, don't go larger than f/8. This will help reduce some visible mechanical limitations, while preserving great depth of field. As a bonus, if your compact camera allows you to choose the "sunny" setting and set your aperture, do it; the colors should be most accurate with that combination. If you have no idea what I'm talking about, choose the "landscape" (mountain icon, typically) setting and move on.

The ability to override autofocus and manually focus before it gets dark are important. Focus at infinity or on a distant object (like the horizon), and turn off autofocus. The ability to focus un-aided after dark is slim-to-none, so getting it right in the light is important.

What focal length to use? Somewhere in the neighborhood of 50 - 60 mm for the wide end, 35mm equivalent; look up conversion factors for your specific camera, compact users. If seated farther away, anything from 70 - 200 mm is acceptable. Don't worry too much about cutting off edges of the bursts. A frame-filling burst will look more spectacular than going too wide and getting tiny spots of color.

Location. It's important. Get to the site of the display early, and scout out locations. Are there any hills to give an advantage of view? Any water to use as a foreground for firework reflections? How about landmarks? Capitol building? Bridges? Metropolitan centers? What direction is the prevailing wind? A headwind is the worst case, a side-wind is best, with a stiff back-wind being an option as well. Knowing wind direction is important, because photos through smoke will not have the same "pop" as fireworks in clear sky.

If finding a suitable location seems impossible, somewhere to capture expressions and spectator heads is fine as well. Foreground elements add a sense of depth and perspective, along with adding to the overall interestingness of the scene.

A couple final notes before the display begins. If using a tripod and your camera or lens has image stabilization, vibration reduction, or any sort of anti-shake capability, turn it off. Tripods and stabilization motors clash, introducing a vibration into the system. Also, the choice to use noise reduction is yours. The exposures are long, which makes noise a problem. However, noise reduction exposes a black frame (black background subtraction) to help neutraliZe noisy pixels. While the black frame is exposing, your chances of missing fireworks increases. I don't use noise reduction, for what it's worth.

Now that it's dark and the show is starting, use the first few volleys to chimp (look at the back of your camera) your exposures. Use a histogram if one is available. It should be mostly black, with a spike up towards the highlights. If you're close enough to hear the tubes launch, it'll be easy to figure out about how long it takes from "fwoomp" to burst. Keep this figure in mind as it will help you get exposures that are tighter around each detonation, wasting less time, and introducing less noise.

In order to capture multiple bursts, use a dark (black) object to carefully block the front of the lens. This will help keep ambient light from washing out the exposure, while allowing several bursts to be captured in one frame. Be warned--several overlapping bursts increase the probability of overexposing areas of the frame. Also, the longer the exposure, the greater the amount of noise.

Armed with the right tools and knowledge, you too can capture great pyrotechnic photographs. Remember to check your settings periodically to ensure nothing has been bumped. Check the histogram for exposure. Finally, enjoy the celebration!

Labels: digital, fireworks, photography

More: Full Post and Comments